on evolutionary instincts

An exploration into how our evolutionary instincts are making our lives worse in the modern world.

sheila

I want to tell you a story. It’s about Sheila, my great^4000 grandmother. Actually, she might be our great^4000 grandmother. If you look far enough back into the Savannah1, the cradle of humanity, it’s hard to see where the knots are tied and frayed, how the tapestry is woven, and how far the roots really go.

But back to Sheila.

Sheila lives in a band of hunter-gatherers, and today, as in most days, they are on a mission for one thing: food.

After a long day of walking, Sheila is tired and weary. Sheila and the other women in her band are tasked with gathering roots and nuts, while the men hunt. But the past few weeks of foraging haven’t reaped anything noteworthy. The nuts in her basket are getting lighter. The little ones are tired and hungry, slowing their pace as their stomachs begin to rumble.

And then, she sees something. At the edge of the river, just a kilometer away, is what seems to be a grove of fig trees. Jackpot.

The band excitedly hurries over, and their suspicions are confirmed. The branches are heavy with the green and purple fruit; their sweet, fermenting scent wafts lazily in the breeze. Today, the band will not go hungry.

But they’re not alone. Baboons shriek on the lower branches, greedily stuffing their cheeks with the fruit, hungry for the same precious calories that Sheila and her clan so desperately need. Men brandish their spears to keep the baboons at bay. The children quickly climb up the trees, tossing figs down to the women, with awaiting baskets in hand.

They know time is of the essence. By tomorrow, the tree will be bare. So today, they gorge.

Sheila digs in. At first, she’s gleeful, even grateful for the food. Her aching muscles thank her for the energy she is delivering to them. But soon, her stomach is stretched to its limits, and a part of her wonders if she should stop.

But her brain is programmed with a different set of instructions. Calories on the Savannah are scarce, to say nothing of sugar, the fastest-acting nutrient her body can process. She may not stumble across another fig tree for months. So tonight, she will keep eating.

Her brain recognizes the sugar on her taste buds and starts flooding her nervous system with dopamine, emboldening her to keep going. MORE, MORE, MORE. She will not stop until there is not a single fig left in the grove.

She’ll lie down that night with a bit of stomachache, but that’s okay. Her brain has done its job. By flooding her with calories, it has increased her chances of surviving and reproducing. It’ll take that excess energy and store it as subcutaneous fat, which will be useful the next time the band’s foodstuffs are running low.

100,000 years later, one of her descendants, a fat-ass kid in Frisco, Texas, used those same evolutionary instincts to rip through an entire family-sized box of Cinnamon Toast Crunch while watching ‘Us’ by Jordan Peele. In a single sitting, he consumed a heroic ~4,000 calories and 400g of sugar.

That fat-ass kid was me. That’s why I’m writing this essay.

why?

It’s not like I was naive. By that point in my life, I had acquired plenty of knowledge on why eating an entire family-sized CTC was not a good idea.

I knew that excess sugar could lead to diabetes, that overeating could lead to obesity, and that whole foods were important. I knew that gluttony was a sin and restraint a virtue. I knew that the morning after, I would feel horrible, both physically and mentally, and regret my actions.

So why did I do it?

My consciousness knew that it was a bad idea. But unfortunately, it was my subconscious that was in control. My monkey brain was in the driver’s seat, and using dopamine as its megaphone, it just kept screaming for more.

But this time, my monkey brain was mistaken. Instead of contributing to my ability to survive and reproduce, it detracted from that same goal. Binging on sugar is a great strategy to die young and never pass on your genes.

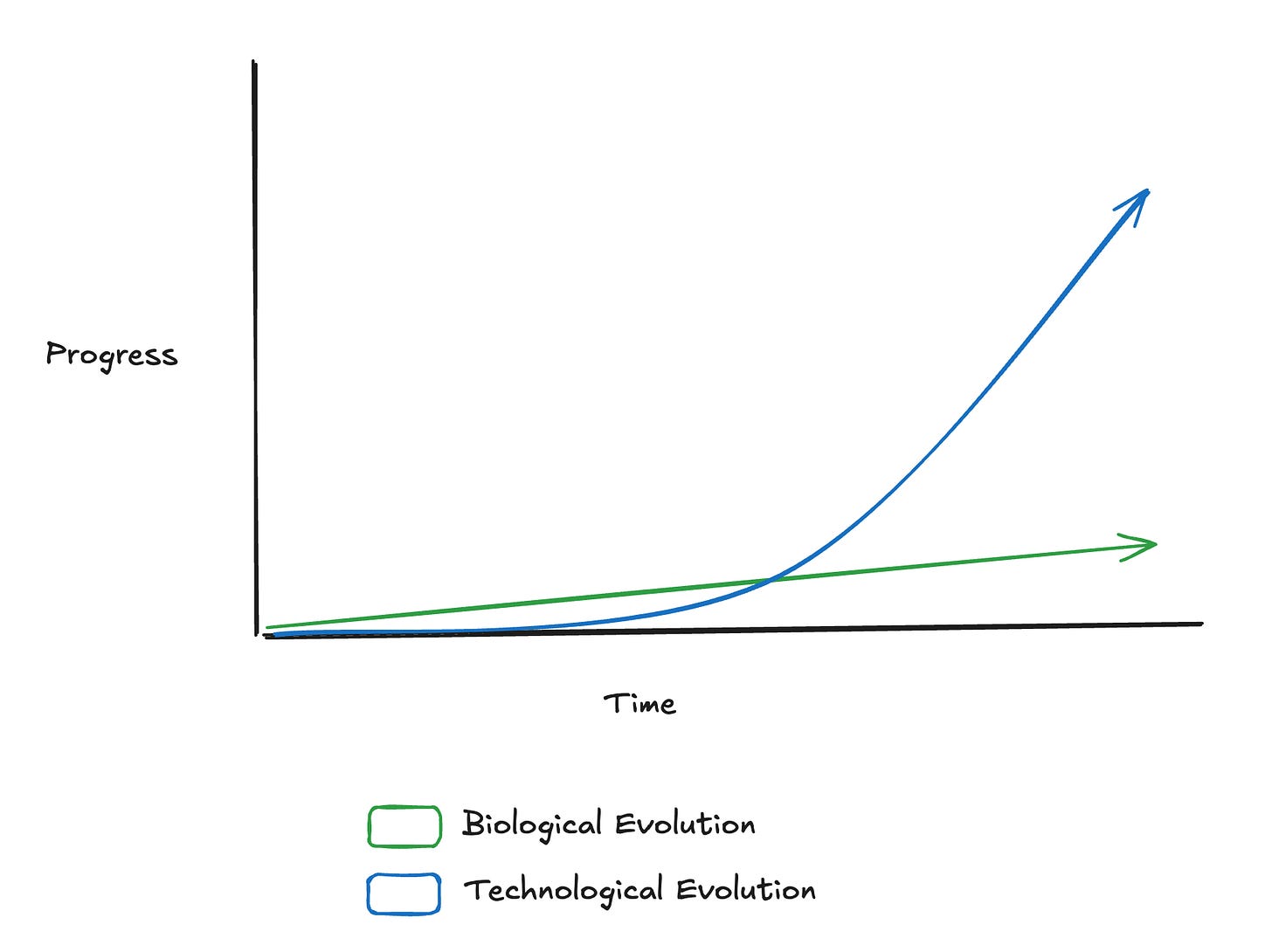

And it isn’t just our instincts to eat. There’s a handful of evolutionary instincts that kept us alive in the Savannah that are slowly killing us today. The reason is the tension between our primal, underdeveloped brains and the rapidly evolving society that humans have constructed around us.

the ‘built’ world (and tension)

On Earth, the human body has proven to be the world’s most effective evolutionary machine. The instincts, chemical regulations, and emotions it produces have not only helped us survive and reproduce, but also enabled us to become the apex predator of the world.

(round of applause to the human race, that’s fucking sick!)

In a world with little to no technological progress, this is a good thing. The makeup of the climate and geography would change, sure, but never faster than the rate of human evolution. We’d be fine, up until an asteroid or supernova said otherwise.

But then technology ‘happened’, and everything changed. Human hunter-gatherers, like Sheila, had always slowly invented technology, from baskets to spears, but around the time of the Agricultural Revolution, our rate of technological progress began to accelerate at a dizzying pace. Our ability to ‘outsource’ evolution to external technology like irrigation and farms, to eventually writing and money, meant that humanity’s ‘real’ evolution became superlinear, while our biological progress stayed linear.

This has led to today, where we carry supercomputers in our pockets, yet still have the same fundamental body as our ancestors. This has led to tension that, in my opinion, causes many of society’s challenges today.

In the ‘built’ world (what I’m calling modern society, with roads, houses, phones, media, grocery stores, etc.), the requisites for survival2 are much different from those of our ancestors on the Savannah.

To survive and thrive in the built world, we must understand all the instincts from our monkey brain and actively fight against them. What follows is a so-unscientific-you-probably-can’t-even-call-it-pseudoscientific explanation of how our evolutionary traits harm us in the modern world.

We’ll explore the most glaring mismatches I’ve identified, why they’re so harmful, and strategies I’m beginning to use to improve my outcomes.

food

Food has been one of my vices for my entire life. I grew up in an Indian family where second and third helpings of chapati and rice were routine and encouraged, and where buttermilk was a staple at dinner. I always had a sweet tooth: as a kid, my mom would fix me a bowl of fruit with a dollop of whipped cream, and I’d sneakily grab the EZ Whip and spray another mountain of whipped cream on top of the dessert.

From those origins, it was no surprise that once I had a car and my own money, food was a challenge. It was too easy to get a Caniac Combo or gummy worms from the convenience store. It was hard to stop eating even when my stomach was full. It was common for me to stress eat whenever I had a bad day.

I’ve spent a lot of time struggling with my relationship to food, and therefore, my weight. I’m not alone: of the American adults aged 20+, 33% are overweight, and 40% are obese! This is frightening, especially given that severe obesity significantly increases all-cause mortality.

How is this possible?

For Shiela, every calorie was painstakingly foraged and hunted by hand. In the built world, we have the opposite problem. There are too many calories present. Calories are wonderfully easy to come by. There are grocery stores and restaurants on every block. A snap of your fingers (and a few bucks) can command you thousands of calories. We even have private taxis for your burritos!

Your monkey brain doesn’t internalize this new paradigm. It still thinks that each calorie is hard-earned and wants to hoard them. It wants you to gorge on food. It believes that it’s helping, just like it helped Sheila. But now, it’s making you fat and slowly killing you.

There’s a reason most foods are laced with sugar. It’s addictive. Food companies want you to spend more on their products to grow their profits, so they add ingredients that make you habitually consume them.

As an aside, it’s important to remember that ‘sweetness’ is not an actual thing. It’s just an arbitrary flavor that your brain has conditioned to send you dopamine when it senses it on your taste buds. Just the same, you’d love to eat cardboard if your brain sent you dopamine every time you chewed on it.

This realization has helped me defeat my sugar addiction.

In the built world, with all its caloric excess, it’s actually more optimal to systematically undereat.

This does not mean to starve yourself, but it does mean turning down a second serving or skipping on the ice cream cone. There are so many calories around you that if you don’t fight back, you will be flooded with them.

When you’re presented with unhealthy options in front of you, and are stupefied by why they seem so enticing, remember that your brain has been conditioned to love sugar and saturated fat.

When you can’t stop eating, remember that your monkey brain wants to hoard food, and that you have the power to stop it.

And tell the monkey brain to step aside. You, the intelligent, discerning human, are in the driver’s seat now.

information seeking

My second biggest vice is social media. I spend WAY more time on social media than I want to. I’m constantly posting some random shit on my Instagram Stories (sorry for being annoying 🤣). I can’t help but doomscroll on Instagram Reels. And I catch myself slacking off on work by scrolling X.

Social media is the digital equivalent of taking a smoke break. When work is hard, I can ‘take the edge off’ by scrolling online for a few minutes. When I’ve had a bad day, I get ‘comfort’ doom scrolling for an hour past my bedtime, holed up under the covers.

A mentor who’s worked on projects with Bytedance (TikTok) told me something that stuck: inside the company, their main competitor isn’t Instagram or Snapchat. It’s your attention. Every minute you spend eating, talking to friends, or lying in bed is time they want to capture. They study when you’re most vulnerable to scroll, and one of their biggest competitors, by name, is your sleep.

Think about that! People are working at TikTok right now who are designing things to make sure that you sleep less. You are under attack. They are happy only when they’ve extracted as much time from your life as possible. They’d love it if you spent 15 hours a day burrowed under your covers, scrolling.

But that’s a story for another day…

Again, our evolutionary instincts have been sinisterly warped to capitalize on our attention.

Our ancestors were rewarded for being curious and collecting more information. The more they knew their environment, the more they would understand where the predators, prey, and natural resources were. The more they learned and experimented, the better tools and strategies they would develop for improved food acquisition, safety, and health.

As a result, this propensity for information seeking was rewarded and passed on into the gene pool. That also means our brain is now wired to collect as much information as it can.

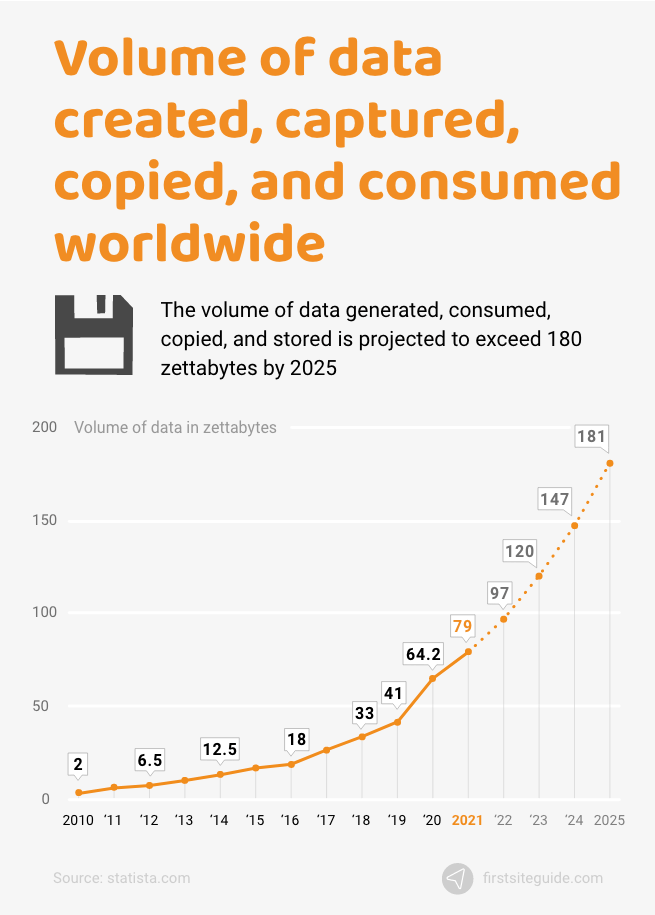

Unfortunately, just like food, information is now abundant. This year, the global datasphere is expected to reach 181 zettabytes. That’s the digital equivalent of 90 quintillion pages, enough to create a stack of paper that would reach across the observable universe. News, social media, blogs, email, messages, games… there’s information everywhere, and it’s all sucking away our attention.

Watch a movie with friends today, and you’ll see that halfway through, someone will pull out their phone and scroll. Fifteen years ago, that would’ve been a blasphemous act. Now, it’s normal. We’re so used to constant stimulation that we can’t focus. Information is bombarding us from every direction, and our monkey brains can’t triage what’s important and what’s not.

Social media has capitalized on our attention. It’s created clever roulette wheels that give us just the right amount of dopamine to keep scrolling. The creators of short-form content know that our brains are irresistibly drawn to their apps, and they design them to make them ever more addictive.

For me, this lack of attention span harms my life. It prevents me from being in the moment with loved ones. It detracts from my ability to produce focused work. And as I alluded to, it drains me of my precious sleep and pumps me with anxiety. Altogether, an unpleasant cocktail!

This information bonanza has addled our monkey brain. It treats information like calories to be hoarded, and is always screaming for more. But consuming too much information is not the way to thrive in this world. Actually, it’s a great way to be anxious and depressed.

We must stop our monkey brain from jumping from tab to tab, from screen to screen. To make our lives better, we must focus more and consume less.

laziness

The human body is always running a cost-benefit analysis on perceived effort and expected reward. It does this because that’s what it needed to do in the Savannah. If it burned too many calories searching for food, it would decrease its chances of survival.

In the built world, this prevents us from doing things we know are ‘good’ for us, making us lazy and prone to procrastination instead. Our monkey brains are great at focusing on the effort part of the equation and can only hazily define the reward. This makes sense given that in the Savannah, the downside risk of burning too many calories (death) was protected at the cost of the upside of gaining a surplus of calories. This is probably why humans have faced loss aversion for eons. We’re built to protect the downside even if we have high expected value.

Practically, this focus on effort instead of reward is enough friction that most people never do anything. They never work out. They never start the project. They never go and say hi to the girl. Our monkey brain is protecting us from the downside risk of wasted energy. Of course, in the built world, expending effort isn’t a problem. Especially given how much we eat, we should probably expend more!

Instead, we need to retrain our brains to focus more on the reward, not the effort. This makes us more likely to do things, to start things, and, as a byproduct, improve our lives.

Scott Adams put it best. This habit is a direct result of our monkey brain’s default mode of thinking.

We need to remember why our monkey brain doesn’t want us to do things, and then do them anyway.

The way Paul Graham says to overcome procrastination plays on this perfectly:

“When I’m reluctant to start work in the morning, I often trick myself by saying ‘I’ll just read over what I’ve got so far.’ Five minutes later I’ve found something that seems mistaken or incomplete, and I’m off.”

Our monkey brain wants the path of least resistance. It will be fine idling away, living a lazy, meager existence. The trick isn’t to wait until you feel like acting; your monkey brain will ensure that moment never comes.

It’s to act despite the resistance. Our ancestors survived by conserving energy. In the built world, we survive by spending it.

risk-taking, tribalism, and status

Remember that I mentioned Sheila was in a band? Being in a group is an important building block of the human experience. We are social creatures because in the Savannah we needed to be. Chances of survival increased if people took turns in the night watch while others slept. If you could specialize labor (the men hunt while the women gather), you’d increase your chances of getting food. And if you stuck with the pack, you’d reap the benefits of tribal knowledge through better technology, geography, and quality of life.

That humans are social creatures is a limiting factor for our quality of life today. In the past, truth-tellers and risk-takers were shunned or killed. As such, everyone knew their place in the hierarchy and was careful not to upset the balance.

Today, truth-tellers and risk-takers are the most rewarded members in our society. Capitalists who take risk in the market have the chance of exponentially increasing their wealth. Scientists who uncover truths about the universe win awards. Wealth and prosperity are driven by new science and technology. Political and religious leaders have more eyeballs on them than ever before. It is the most rewarding time in history to take risk.

But not only are the upsides so high, but the built world has also provided unprecedented downside protection.

Today, 99% of risk is financial, not physical. Our lives are never in danger! Moreover, based on your privilege, education, and country of origin, your safety nets are absurdly strong. I would posit that if you live in the United States, are educated, and aren’t addicted to drugs or have a crippling illness, your downside for risk-taking is basically 0.

Let’s think about taking a risk as a (childless) 20-something-year-old in America. Imagine you quit your job, liquidated your savings, and started a career as a traveling bagpiper. The absolute worst thing that could happen is that you can’t kick it on tour, you lose all your money, lose your job, and can’t pay rent. My assertion is that you’re sufficiently diligent, you can change all those things in < 3 months.

Status is equally non-relevant.

For example, if you are a law-abiding citizen and live in the first world, people’s opinions of you don’t matter. Unlike the past, your ‘hierarchy’ will never affect your ability to get food or shelter. If you have money, people will trade you for those things. And money doesn’t care about your status. The money you acquired from an evil dictator in Russia and the tooth fairy count the same at the grocery store.

You can be as weird as you want, as neurodivergent as you want, as long as you abide by the laws, your life will never be at stake.

If you wanted to, right now, you could start crawling around your neighborhood on all 4s. Nothing would happen. Don’t break the law, and you can do whatever the fuck you want.

Still, even though the calculus of risk-taking and status has changed, people’s decision-making hasn’t. We’re still so tied to what other people’s perception of us is. We feel that we must conform to what society, our family, and friends do — we must work the high-status jobs, practice the popular political belief of the day, or obsess over whatever fad is the craze3.

But all these perceptions are just that: perceptions. The only way they affect our lives is if we allow them to. Our monkey brain will plead for us to do just that. But in the built world, you can live a wonderful life outside of the bounds of perception.

I’m obviously talking my book here, but as soon as I was able to stop letting my brain map risk, reward, and status to its rudimentary understanding of life, I was able to do things I cared about (like starting a company), which made me happier.

I think this would have equally profound benefits for everyone reading this.

short-term gratification

An overarching flaw of our monkey brain (and much of the theme of this essay) is its bias towards short-term gratification. On the Savannah, it’s hard to think long-term when every day is a struggle for survival. Why should something in 15 years matter? I might starve or get eaten TODAY.

This means our body is centered around gaining short-term rewards (mainly dopamine), and isn’t sure how to internalize long-term rewards.

So we do things that please us in the short term (junk food, porn, social media) and harm us in the long term; these things are usually at the detriment of long-term health, fulfillment, family, and career goals. It’s not our monkey brain’s fault. It can’t conceptualize long-term gratification, so it doesn’t know how to reward it.

But it’s true that in the built world, the best things in life happen over multi-year or even multi-decade time horizons:

Building the body of your dreams

Pursuing mastery in a craft

Creating a long-term partnership and family

Building a great company

So to ensure fulfillment, we need to overcome our monkey brain’s inclinations and hammer home the long-term view. Impatient with actions, patient with rewards. Delay gratification as much as possible, sacrificing the short-term (cheap) rewards4 for long-term (wholesome) rewards.

so what

I’m not here to tell you how to live life. You should do whatever makes you happy. As long as you don’t get in my way of achieving that goal, I won’t get in the way of yours.

What I am telling you, what I am begging you, is that you should choose. You should be in the driver’s seat. You should not be at the whim of your monkey brain. It’s a dumb, little fucker, and its goal is NOT to make you happy.

It has an entirely different incentive structure than you do, and if you give it control, it will drive you off a cliff. You’ll sleepwalk through your entire life, scrolling through TikTok while waiting for the tenth DoorDash of the week, wondering why something is missing in your life. (Okay, I lied, I will tell you that you shouldn’t live your life like that, it sounds miserable.)

I want you to be in the driver’s seat because you are perfectly capable of having an awesome life. And for you to do that, you have to be aware of all the roadblocks in front of you. I spent a lot of time beating myself up for my struggles with food and social media without fully understanding the root cause. I always thought it was a failing of my character and discipline. And to be sure, there’s a lot that it does reflect on me, and there’s a lot I can do better, but it makes it a lot more manageable when I realize that there’s a dumb little monkey brain actively preying on my downfall.

If we can understand the underlying reason why our brain makes certain decisions, then hopefully we can steer it to make better ones. And if we can steer it to make better ones, then hopefully all those little decisions can lead to a better life.

That’s what I’m trying to do with my life. Hopefully, this helps you do that better for yours. Good luck.

When I mention ‘the Savannah’ in this essay, I don’t mean the actual biome that still exists in Africa today. I mean it more in the symbolic sense of the lives of our first hunter-gatherer ancestors.

I am using survival in the loosest sense, mostly meaning to thrive and live a good life. However, for some people, this negatively contributes to their ability to fulfill their evolutionary goal of surviving and reproducing.

The trends are always equally fun and stupid: silly bands, American Girl dolls, Labubu, boba, Dubai chocolate, Supreme box logos, Popeyes chicken sandwich. History doesn’t repeat; it rhymes.

If there’s any more reason to delay gratification, I think that you pay a karmic debt when consuming too many short-term rewards like DoorDash and TikTok. I don’t know how or when you pay this debt, but I do believe that at some point, you have to pay the piper.

Also, on laziness, I think Buddhism captured it better. Laziness (or what Buddha calls sloth and torpor) is indeed unwise attention to the effort rather than the outcome (benefit), but conversely, restlessness and worry, is unwise attention to the outcome rather than to the effort (Paul Graham's trick is mainly to address the latter). I think most people suffer from both.

For completeness, Buddha also calls out unwise attention to the beauty (your writings on the excessive food and information) and unwise attention to the fault (which social media company used against us through the information that they provided us), as well as unwise attention to the uncertainty.

Good writing, but "one of her descendants" not "one of her ancestors" in the paragraph starting with "100,000 years later".